How cognitive diversity can help us win wars

On leadership and while at it, beating the Russians and Chinese

Winning starts with diversity in our people. Now you probably think of gender, skin color or religion, but that is not what I mean. What we need is cognitive diversity. Cognitive diversity means that within a group of people there is a diversity of reference frames and models about our world. Why is this important? Let me explain with the help of a personal anecdote.

During an international exercise, I was working in the current cell within the brigade as head of the intelligence section. In the scenario, we were fighting an offensive battle together with two other brigades under the leadership of a division, but the offensive got stuck at a certain point, so everyone was looking for a way to maintain the momentum. One of my corporals was charged with the task of continuously monitoring the enemy positions on the bird table (map). Somewhere in the late hours he gets into a conversation with the G3, a lieutenant-colonel, and asks why we don't try to break through at a specific point on the front. After all, this is where the enemy is at its weakest. Not much later, everyone in the current cell is bent over the map and concludes that this is indeed an opportunity. This is then presented to the brigade commander who is also convinced and in turn informs the division commander. The breakthrough and renewed offensive succeed and the momentum of the division is restored. The insight of this corporal ultimately determined the success of an entire division. Not only was his insight special, but especially the courage this corporal showed to share this insight with someone who is hierarchically far above him. I have often thought of this moment. Did I as a leader give him enough space to share his insight? How often have I created a situation in which my team members did not feel the freedom to make a contribution, while this could probably have been a very useful contribution?

The example above exposes two problems. The first, a team of clones all think the same and therefore only see a limited number of solutions, or none at all. In other words, we are not cognitively diverse enough. The second problem is that we naturally create hierarchical cultures within groups of people in which not everyone is allowed or dares to contribute. So even if we are cognitively diverse, team members must feel free to share information or insights. This article explains why and how cognitive diversity can give our armed forces a significant advantage over an opponent. Because as General Petraeus already stated: “The most important weapon a soldier carries with him (or her) on the battlefield is his (or her) mind”.[1]

How soldiers can help an oncologist. Nowadays, there are few problems that we as humans can solve alone. Almost all challenging problems that we have to solve are complex and require the cooperation of groups of people, teams. Whether this concerns the design of an unmanned weapon system or how armed forces should organize its army formation, no one can do this alone and so we have to work together. However, when a group consists of people with the same frames of reference (e.g. experiences and knowledge) then almost everyone thinks the same and therefore sees a limited number of possible solutions. Matthew Syed sketches an interesting example in his book ‘Rebel Ideas’ where he explains how a military insight can help an oncologist. I have quoted this example before in my post on why we need to look ‘Beyond the Art of War’.

The analogy provides a new perspective that helps to find a solution to the problem.[2] This example is not only beautiful because a military insight can apparently solve a medical problem, but it also shows that the reverse is probably also possible. Insights from disciplines outside the military domain can lead to military solutions. The American pilot and military theorist, John Boyd, known for the OODA-Loop[3], stated decades ago that soldiers should not limit themselves to just military knowledge and insights. In practice, however, we are often inclined to attract more experts to solve a problem. Instead we should do the opposite, put together a more diverse team.

A team of ‘clones’ or ‘rebels’?

Syed explains that homogeneous groups systematically underperform. This is because homogeneous groups not only share each other’s blind spots but also reinforce them. Tests show that teams with (only) one outsider perform many times better than homogeneous groups. On average, these teams have the right answer to a given problem 75% of the time, while a homogeneous group has 54% and individuals only 44%.[4] Philip Tetlock and Dan Gardner explain in the book ‘Superforecasting’ that this applies in particular to problems where predictions have to be made.[5] Something that is at the heart of the military profession, whether it is creating courses of action (COA) or when we think about how to recruit more personnel.

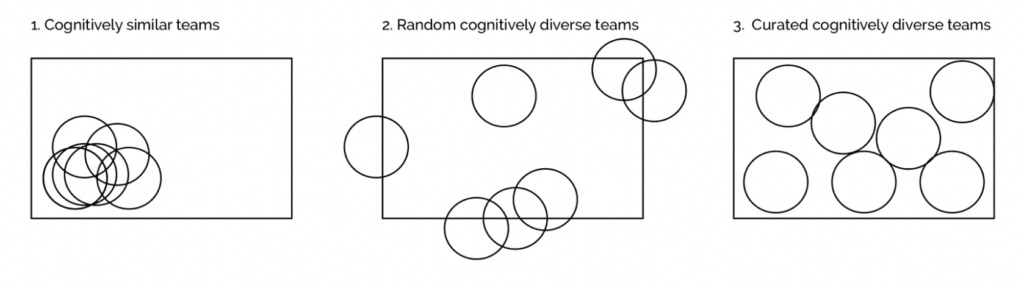

Every person has a certain reference frame in which his or her worldviews, experiences and knowledge can be summarized. If you were to visualize this as a circle, where each circle is the total reference frame of one of the team members, then you can visualize this as in figure 1.1. A team of 'clones' has a large overlap of reference frames as can be seen in the first figure. Think of a group of surgeons or oncologists who all graduated from the same university or a group of officers from the same class of the military academy. Figure 1.2 shows a team with various frames of reference where the total surface area of the frame of reference is larger but where this is arbitrary and therefore not always useful for the task at hand. Figure 1.3 shows the most desirable composition, a selected cognitively diverse team.[6]

A cognitively diverse team is not the same as a team with a diverse gender, religion or cultural background, but there is a clear connection. Women most likely have a completely different frame of reference than men, despite the fact that recent research has shown that there are few visible differences between male and female brains.[8] [9] Women, on the whole, have different interests and a different role in social groups than men and therefore probably have had different experiences up to the moment they enter military service. Someone who grew up in another culture will also have a different reference frame. In an experiment in which an aquarium was shown to an American and a Japanese. Both were asked what they observed. The American named the fish, while the Japanese spoke about the context, such as the current, the rocks and water plants. When in another experiment the fish were swapped, this was not noticed by the Japanese test subjects, but was noticed by the American. Conversely, changes in the context, such as the underwater scene, were not noticed by the American subjects, but were noticed by the Japanese. Culture can cause the same image to be perceived through a different filter.[10]

However, we should not be misled by external characteristics. Someone with a different appearance, for example because both his parents have an Asian background, could just as well have grown up in the US and studied at the same university as his native US colleague and thus have an overlapping reference frame. On the other hand, someone with the same external characteristics can have a completely different reference frame and thus be cognitively more diverse.

“The deepest problem of homogeneity is not the data that clone-like teams fail to understand, the answers they get wrong, the opportunities they don’t fully exploit. No, it is the questions they are not even asking, the data they haven’t thought to look for, the opportunities they haven’t realized are out there.”[11]

The way we select people is based on meritocracy, where we focus on competency and skills. However, practice shows that this causes us to converge towards clone-like teams with people who, for example, studied at only specific universities. Syed gives an example of the recruitment and selection of the CIA in the years leading up to 9/11, where the emphasis was also on competency and without diversity. The result was that there were hardly any people with an Islamic background working at the CIA. The many studies after 9/11 showed that the CIA missed important signals of the impending attack, simply because the religious context of this terrorist group was a blind spot.[12] The trick is to select on the basis of both competency and cognitive diversity.

One would expect that it would be more effective to have a team of like-minded people, and that is true when you only look at the process. These homogeneous teams are being experienced as more pleasant, while diverse teams lead to much more discussion and disagreement.[13] However, when you look at the results, it turns out that diverse teams are structurally more successful than homogeneous teams with the most intelligent people.[14] Of course, when composing a team, we choose a team that suits us and does not lead to friction. We also do not quickly consider teams with friction as successful teams; it is not for nothing that we speak of ‘machines’ when teams know how to work together well. What if you are faced with the choice of composing a team, such as the staff of a combat unit or headquarters, with which you have to go into battle? Would you then choose a machine, a team of clones, that is good at what machines normally do, a repetitive process? Or would you rather choose a team of rebels who are able to solve complex problems that you could not have foreseen? I prefer to have an opponent who behaves like a machine because it is much more predictable.

How leadership is the problem and the solution at the same time.

Cognitive diversity is only part of the solution. Leaders have a great influence on the extent to which diverse insights are shared, or not. Syed explains that people naturally seek or create a hierarchy within a group with a formal or informal leader. Put a group of people together and within a short time some form of hierarchy will arise.[15] A clear hierarchy with a strong leader can be effective when decisions have to be made under (time) pressure, which is something military personnel understand all too well. However, this hierarchy can also have negative consequences. Syed gives the example of flight United Airlines 173 on December 28, 1978. Due to a technical defect in the landing gear, the plane cannot land. While the pilot is busy solving the problem, the co-pilot sees that the fuel is slowly running out. The co-pilot initially does not dare to report this to the captain, because he thinks the pilot will likely have seen it himself as well. The culture in the aviation sector at that time was very hierarchical, people do not question the captain's insight. When the level slowly became critical, the co-pilot finally reported the low fuel level, but in a concealed manner, as appeared from the recordings from the cockpit. Only when the engines died did the co-pilot explicitly state that the fuel had run out, but then it is too late. The plane crashes and more than 20 people die. This example is unfortunately not an exception.[16] Social relationships matter. Even when crucial information has to be shared, people may not dare to share this information.

Back to my own experience at the brigade headquarters. What if a corporal receives important information but does not dare to share it? I am convinced that even majors were not always prepared to share their insights with a lieutenant-colonel. It is crucial to share relevant information with each other, especially within a headquarters or command post. The above example shows that even objectively factual information is not shared when there exists a culture where it is inappropriate to ‘challenge’ the leader. Information is one thing, but insights or ideas are much more dangerous to share. What if you are wrong?

When sharing ideas, people often listen to what the manager says or might even think. This is also called the HIPPO effect: Highest Paid Persons Opinion.[17] In the military, you could replace ‘Paid’ with ‘Ranking’, HIRPO. When such a person starts the meeting with his or her ideas, the willingness to share other ideas is subconsciously dampened, significantly. Unit commanders are often consciously assigned this role and it is even made explicit in command procedures. This reinforces the HIRPO effect even more. To prevent this effect, companies such as Amazon apply techniques to motivate team members to contribute authentically, for example by always speaking last as a manager or by having each team member contribute individually on paper first.[18] However, leaders are still needed, especially in diverse teams. Who ultimately decides which idea should be implemented, and how do you determine that?

Soldiers must be able to quickly switch between different leadership styles. Unlike the commercial world, the armies are faced with opponents who misleads us and try to out-maneuver us. But above all, there is no second place. Losing is not an option. A military leader must be able to lead under difficult circumstances where decisions sometimes have to be made in a short time. This often requires a more direct style of leadership. On the other hand, there are also situations where there is more time to think about solutions and involve every brain in the search for solutions. The art of leadership is finding a balance between these two extremes. You want to create a situation in which your leadership is not questioned, but where every team member also feels free enough to share their information and insights, even when they differ from the rest. This is also called Command Climate.

“Responsibility cannot be delegated, but cognitive thinking power to arrive at the best solution can.”

In addition, it is important to consciously think about the composition of your group or team. Even if you have created a favourable starting situation by putting together a diverse team, you must prevent yourself from getting a team of clones, for example through the ‘HIRPO effect’.

Another variable: culture

Nowadays it is self-evident that the armed forces operate internationally. In almost every scenario NATO forces fight alongside, or under the leadership of, an ally. As the previous example about the difference between the perception of an American and a Japanese person already indicated, culture is relevant. Many cultures are more hierarchical than for example the Dutch culture. Erin Meyer explains in her book ‘The Culture Map’ that every culture looks at leadership in a different way and that you can divide this on a scale between egalitarian and hierarchical (figure 1).[19] The Netherlands is positioned to the left of the egalitarian side on this scale, while some of our allies are positioned more to the right. Within an international context, there is automatically a more cognitively diverse team, but a more hierarchical leadership culture may dampen the input of these diverse insights and ideas. Our potential opponents, Russia and China, on the other hand, are on the other side of the spectrum and are clearly more hierarchical.

Meyer gives an example of a Danish manager who explains how different leadership is in Russia. Normally he states: “..the best way to get things done is to push power down in the organization and step out of the way.” When this Dane had to lead a Russian team, he was not taken seriously. His staff puts him on a pedestal and constantly asked him how he wanted them to do the job. His staff expected him to have the answers.[20] After three years he says: “…I have to maintain a greater distance with my staff and fulfil a type of paternalistic role that was new to me. Otherwise, my staff simply would not respect me or, worse, be embarrassed by me.”[21] The question now is, how can cognitive diversity go hand in hand with a Russian culture as described above? Would a Russian corporal dare to share his insights with a lieutenant-colonel? This culture must logically have a negative effect on the willingness of subordinates to share information, insights or ideas with leaders. This is also what we probably observe in the Russian army in the current conflict in Ukraine. Not only is there little room for discussion and creativity, the decision of the leader is the law. On top of that, there is a culture in which lying is institutionalized.[22] [23] Mick Ryan for example explains in his recent book ‘The War for Ukraine’ the following: “Fear of reporting honestly and exposing bad news on the battlefield is a significant inhibitor in Russian battlefield and strategic adaptation.”[24]

That the leadership culture in countries like Russia and China probably offers little room for cognitive diversity is an additional reason for NATO to make optimal use of cognitive diversity. Advantages are relative to your opponent and we can increase this relative difference. Potentially, we can solve problems faster and more creatively, or create them for our opponent.

Conclusion

Cognitive diversity produces innovation and better results. However, cognitive diversity only works when people are prepared to share information, insights or ideas. This requires a leadership style that allows or even strengthens this sharing of insight and ideas. For this, our military leaders must have a broader range of leadership styles and know when to use them. As the example with the corporal showed, solutions are often within reach, but we do not always create an environment in which these solutions are shared. Let us use the knowledge and experience of more than just the one brain of the commander or manager. A team of clones is probably more pleasant to lead than a team of rebels, but in war only one thing counts: winning. I would rather have a handful of rebels than ten times as many clones. Cognitive diversity is the Achilles heel of our potential opponents such as Russia and China. By using it ourselves we can both exploit the weakness of our opponents and increase our potential strength. What we need for this is nothing more than a different mindset. People solve problems, or can create them for our opponents. Let’s make better use of them.

The views expressed are those of the author and do not reflect the official position of the Armed Forces.

This post is an English translation of the original which was published by me in the Dutch magazine for Military officers called Carré in December 2024.

[1] Philip E. Tetlock, Dan Gardner, Superforecasting: The Art and Science of Prediction (Audible Studios, 2015)

[2] Matthew Syed, Rebel Ideas: The Power of Diverse Thinking, P17

[3] OODA: Observe, Orient, Decide, Act. Frans P.B. Osinga. Science, Strategy and War: The Strategic Theory of John Boyd

[4] Matthew Syed, Rebel Ideas: The Power of Diverse Thinking, P21

[5] Philip E. Tetlock, Dan Gardner, Superforecasting: The Art and Science of Prediction

[6] Matthew Syed, Rebel Ideas: The Power of Diverse Thinking, P41, 49

[7] Matthew Syed, Rebel Ideas: The Power of Diverse Thinking, P41, 49

[8] https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-019-00677-x

[9] Matthew Syed, Rebel Ideas: The Power of Diverse Thinking, P92.

[10] Study (2001) by Nisbett and Masuda. Bron: Article by Lea Winerman, The culture-cognition connection: Recent research suggests that Westerners and East Asians see the world differently–literally. American Psychological Association, February 2006, Vol 37, No. 2 https://www.apa.org/monitor/feb06/connection

[11] Matthew Syed, Rebel Ideas: The Power of Diverse Thinking, P55

[12] Matthew Syed, Rebel Ideas: The Power of Diverse Thinking, P55

[13] Matthew Syed, Rebel Ideas: The Power of Diverse Thinking, P21

[14] Matthew Syed, Rebel Ideas: The Power of Diverse Thinking, P60

[15] Matthew Syed, Rebel Ideas: The Power of Diverse Thinking, P76

[16] Matthew Syed, Rebel Ideas: The Power of Diverse Thinking, P77-79

[17] https://jeffgothelf.com/blog/highest-paid-persons-opinion/

[18] https://www.cnbc.com/2023/02/04/jeff-bezos-secret-to-success-boss-should-always-talk-last-in-meetings.html

[19] Erin Meyer, The Culture Map: Decoding how people think, lead, and get things done across cultures, P125

[20] Erin Meyer, The Culture Map: Decoding how people think, lead, and get things done across cultures, P118

[21] Erin Meyer, The Culture Map: Decoding how people think, lead, and get things done across cultures, P142

[22] Vranyo (враньё): Ik lieg en ik weet dat jij weet dat ik lieg, maar dat interesseert mij niets.

[23] Luitenant-kolonel Christiaan Kamphuis Bsc, Vranyo, Militaire Spectator, 17 juni 2024 https://militairespectator.nl/artikelen/vranyo#_ftnref7

[24] Mick Ryan, The War for Ukraine: Strategy and Adaptation under Fire, P133

Image 1: https://stockcake.com/i/military-strategy-session_1232374_1110111

Image 2: https://stockcake.com/i/strategic-military-planning_523674_432679