“The most important 6 inches on the battlefield is between your ears”

Why you should be interested in neuroscience.

For those that are already familiar with my writings, you know I am fascinated by how our brains work. From a military perspective this may seem odd, neuroscience is clearly within the realm of biology. The art and science of war are something different altogether, right? No it isn’t. Just like John Boyd argued, we need to look at other sciences as well. The delineation between the different sciences is relative and more of a social construct than an actual explanation of how the world works.

One military theorist, who’s work I really admire, argued that the workings of the brain are not relevant to military decision-making since this is about groups of people, not individuals, and thus the realm of psychology and sociology. Of course, you cannot reduce everything to how one brain works. But one way or another, it is all about people, who make decisions and who are able to cooperate or not. The latest discoveries in neuroscience however explain so many things that sociology and psychology are struggling to explain that we cannot ignore the implications.

Therefore, I am convinced that understanding our brains is important. For it determines how we view war, how we adapt to it, how we make decisions, how we can deceive our opponents, but also more basically in how we can train fighter pilots to multitask while pulling G-forces or have infantry change their magazine unconsciously. Understanding how you yourself think, your soldiers, or your adversary, is probably the most important thing there is. Or as General (Jim) Mattis is believed to have said:

“The most important 6 inches on the battlefield is between your ears” General J. Mattis

There are in my opinion five books that are really worth your time when you want to understand how our brains work. There are of course thousands of books on our brains, but many give you an outdated picture on the brain. These five books however seem to converge on the same novel ideas, which are revolutionizing current theories on how our brains work. I’ll give you a brief summary of the key points discussed in these books. I have taken the liberty of making a priority of which books are most important and most accessible to read.

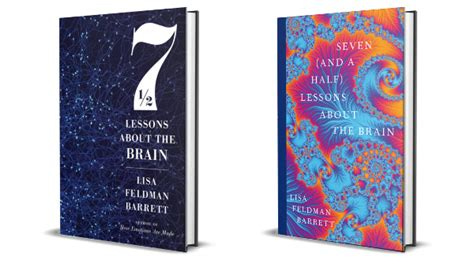

#1: Seven and a Half Lessons About the Brain, by Lisa Feldman Barret

This book is by far the most influential and accessible book there is on how our brains work. Barret has also written the book ‘How Emotions are made’, but this shorter book is not only easy to read, but also focusses on the main lessons, seven and a half to be precise. She explains that our brains are not made for thinking but regulating the body. It constantly predicts and adjusts bodily resources to keep you alive efficiently. Another important conclusion: our brains predict (almost) everything. Most interestingly, she explains this concept by using an example of a soldier that makes the wrong prediction in a stressful situation, mistaking a shepherd for a terrorist.

Just one quote that made a lasting impression on me, and of which the impact is far greater than many assume:

“What happens next still astounds me, even as a neuroscientist. If your brain predicted well, then your neurons are already firing in a pattern that matches the incoming sense data. This means this sense data itself has no further use beyond confirming your brain’s predictions. What you see, hear, smell, and taste in the world and feel in your body in that moment are completely constructed in your head. By prediction, you brain has efficiently prepared you to act.”[1]

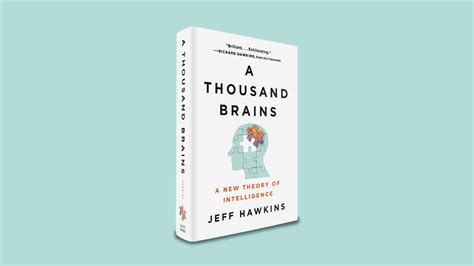

#2: A Thousand Brains: A new Theory of Intelligence, by Jeff Hawkins

Jeff Hawkins has formulated a new theory on how the brain works. He believes that if we want to create a truly artificial intelligence (AI), the best strategy is to emulate how our brains work. Brains are often compared to how computers work, but this analogy is obviously false and misleading. Hawkins argues that our brains use a thousand models to build understanding. Intelligence is not a single, centralized process but arises from many independent models distributed across the neocortex. Each cortical column (a tiny processing unit) builds its own model of the world and contributes to our overall perception and decision-making. Hawkins also argues that learning is driven by movement and prediction (just like Barret argues). The brain continuously updates its models of the world by moving through it, either physically or mentally. It makes predictions, compares them to sensory input, and adjusts its models accordingly, similar to how we learn a new object by touching it from different angles. I have already written about this book in an earlier post called “Our brains are the measure of all things”.

What I like most about this theory is that it also provides an explanation for why and how the brain makes predictions: by creating models (using cortical columns) and by picking the correct model by way of ‘voting’.

“Our reality is similar to the brain-in-a-vat hypothesis; we live in a simulated world, but it is not a computer – it is in our head.”[2]

You can easily find some videos online of Jeff Hawkins explaining how his theory works, great to watch if you don’t fancy reading the entire book.

#3: The Experience Machine: How our Minds predict and shape Reality, by Andy Clark

Andy Clark is a cognitive philosopher who argues that our brain functions as a dynamic prediction machine (again, just like Barret and Hawkins argue). He challenges the traditional view of the brain as a passive receiver of sensory information. Clark argues that our minds actively construct reality by generating continuous predictions based on past experiences. These predictions are then matched against incoming sensory data, shaping our perceptions and experiences. This process suggests that perception involves a form of "controlled hallucination", where our expectations shape our sensory experiences. Therefore, strong predictions can sometimes lead to hallucinations. Something Barret (also) explained in her example of the soldier that mistakes the shepherd for a terrorist. Clark also explores how our understanding of this predictive framework can help us treat mental health issues.

Clark also provides an interesting theory on the integration brains and technology. He calls this the concept of the "extended mind," suggesting that tools and the technologies we use can become integrated into our cognitive processes. Our brains predict and adapt to these extensions, effectively incorporating them into our perception of reality. This perspective sheds light on how technology influences our thoughts and experiences.

To conclude, the experience machine explains why experience matters, and thus for those in the military, why training (experience) matters.

#4 Being you: A new Science of Consciousness, by Anil Seth

I have already written an extensive post about this book, where I compare it with some of the ideas offered by Jeff Hawkins, in “Why we only experience ‘Controlled Hallucinations’”.

Seth (also) argues that the brain is constantly making predictions about the causes of its sensory signals, predictions that cascade in a top-down direction through the brain’s perceptual hierarchies. He explains “sensory signals – which stream into the brain from the bottom up, outside in – keep these perceptual predictions tied in useful ways to their causes: which is whatever you are observing. These signals serve as prediction errors registering the difference between what the brain expects and what it gets at every level of processing. By adjusting top-down predictions so as to suppress bottom-up prediction errors, the brain’s perceptual best guesses maintain their grip on their causes in the world. In this view, perception happens through a continual process of prediction error minimization.”[3] This element of prediction error minimization is what makes Seth’s theory a valuable addition to the books mentioned above, because it explains how our brains learn. This is incredibly important, since this seems to be the exact same mechanism that we see (or possibly need) when we want to become adaptive as an individual or organization, see my post on “Adaptation: a military necessity”.

#5 Determined: A Science of Life without Free Will, by Robert M. Sapolsky

This book is something different than those mentioned above, because it does not solely focus on how the brain functions. Robert Sapolsky is also a neuroscientists, but also a primatologist by the way, which makes for interesting examples. Moreover, he writes with humor and with a very accessible style. By using a wide range of interdisciplinary scientific research, he argues that there is no such thing as ‘Free Will’, it is just an illusion. Whether you agree with him or not, this book made me wonder how entrenched this concept is in our concepts of (military) decision-making. What do we mean when we say that we ‘make a decision’? How relevant is the D of Decision in concepts like the OODA(loop)[4]? Is it more about communicating what we together decide, or is it about actually deciding between for example two alternatives? Sapolsky explains brilliantly how decisions are being formed, not only in your brain, but also socially. To conclude, this book will make you doubt whether we make our choices as consciously as we think we do. And of course, our brains have an important part to play.

[1] Lisa Feldman Barret. Seven and a Half Lessons About the Brain, P74

[2] Jeff Hawkins. A Thousand Brains: A New Theory on Intelligence, P175

[3] Anil Seth, Being you: a new science of consciousness, P82, 83

[4] OODA: Observe-Orient-Decide-Act. A decision-making model created by John Boyd.

Bibliography:

Andy Clark. The Experience Machine: How our Minds Predict and Shape Reality (New York: Pantheon Books, 2023)

Lisa Feldman Barret. Seven and a Half Lessons About the Brain (London: Picador, 2021)

Jeff Hawkins. A Thousand Brains: A New Theory on Intelligence (New York: Basic Books, 2021)

Robert M. Sapolsky, Determined: A Science of Life Without Free Will (New York: Penguin Press, 2023)

Anil Seth. Being you: A New Science of Consciousness (London: Faber & Faber Ltd, 2021)

I have repeated and rephrased this on more than one occasion as "sometimes the schwerpunkt is between the ears"