My hypothesis is that armed forces tend to focus on flexibility instead of adaptiveness. The capability to adapt is perhaps one of the most important capabilities that any army should develop and nurture. In this post, I will explain the difference between flexibility and adaptiveness. I will argue that we need to change the way we train our troops, and I’ll provide a possible avenue of approach on how to achieve this.

There are broadly speaking two strategies you can pursue in becoming adaptive. The first is to anticipate the next war accurately. This way, you can not only prepare for it more efficiently, you know what to expect. The second strategy is to create a culture within the armed forces that is in itself adaptive, not matter what the future war will bring. Let’s start with the first strategy.

“All that remains to be said [of this important continuity in war] is that military institutions must nurture the development of an institutional learning capacity before conflicts if they wish to adapt effectively during war.”[1]

Anticipating the next war

There is a saying that we often fight the last war and are thus per definition ill-prepared. The war in Ukraine is a perfect example of this. This is true for both sides of the conflict, as Mick Ryan shows in his book ‘The War for Ukraine: Strategy and Adaptation under Fire’. Although the Russians have likely planned the invasion of Ukraine well in advance, they not only failed to predict the amount of Ukrainian resistance, but the Russians also clung to an image of warfare that was perhaps already obsolete before the war started. In other words, they were slow to adapt.[2] To name two examples, the overall transparency of the battlefield and the vulnerability of employing helicopters across the Front Line of Own Troops (FLOT) were highly underestimated. This resulted in many downed helicopters and the destruction of command posts or dense troops concentrations in the beginning of the war.[3] [4] [5] To be fair, most Western armies neither anticipated these changes at the outset of the war. As of now, doctrines describing air assault operations using helicopters have still not been changed, despite the widespread acceptance that no army will be executing these operations is Large Scale Combat Operation (LSCO) anymore.

History has shown us that we continue to get (the next) war wrong. Sean McFate argues in his book ‘Goliath: Why the West isn’t winning. And what we must do about it’ that this has to do with what he calls the war futurists. “These are the people who dream up future war scenarios. They fill our heads with the make-believe battles of tomorrow that drive strategic decisions today.” Moreover, “Lawrence Freedman, a preeminent war scholar, surveyed modern history and found that predictions about future war were almost always incorrect.”[6] There are two types of futurists, McFate explains: the patriots and the technophiles.[7] In short, the patriots envision the next war as being like world war II, just with newer technology. The technophiles envision a world where technology will change everything. They envision a world of robotics, AI and often incorporate elements that are more akin to Hollywood than real life.[8] Both of these views are perhaps not entirely wrong, but they also have a terrible track record of making good predictions. Few military theorists have made good predictions. McFate names Mitchel and Fuller as two examples that did prove to be (partially) correct.[9] The problem is that it is extremely difficult to make good predictions about the future character of war. The same is true for making economic or market predictions, yet we nonetheless continue to feel the urge to make these guesses.[10] I am therefore inclined to think that we should not bet our money on the futurists. What if we accept that we will always be surprised to some degree? This would require us to focus on being adaptive as a necessity in itself.

Becoming adaptive or merely flexible?

It is easy to claim you are adaptive, but it is something else to actually become adaptive. People are creatures of habit and we like our world to be predictable. Most get the idea of adaptation wrong and mistakenly think this is analogues to being flexible. This is understandable because the differences can be blurred.

Flexibility refers to adjusting responses within a known range of possibilities. A flexible system or person can switch between predefined strategies but does not create fundamentally new ones.

Adaptability refers to the ability to develop new solutions for novel problems, meaning the system or person can think and act beyond prior constraints and innovate.

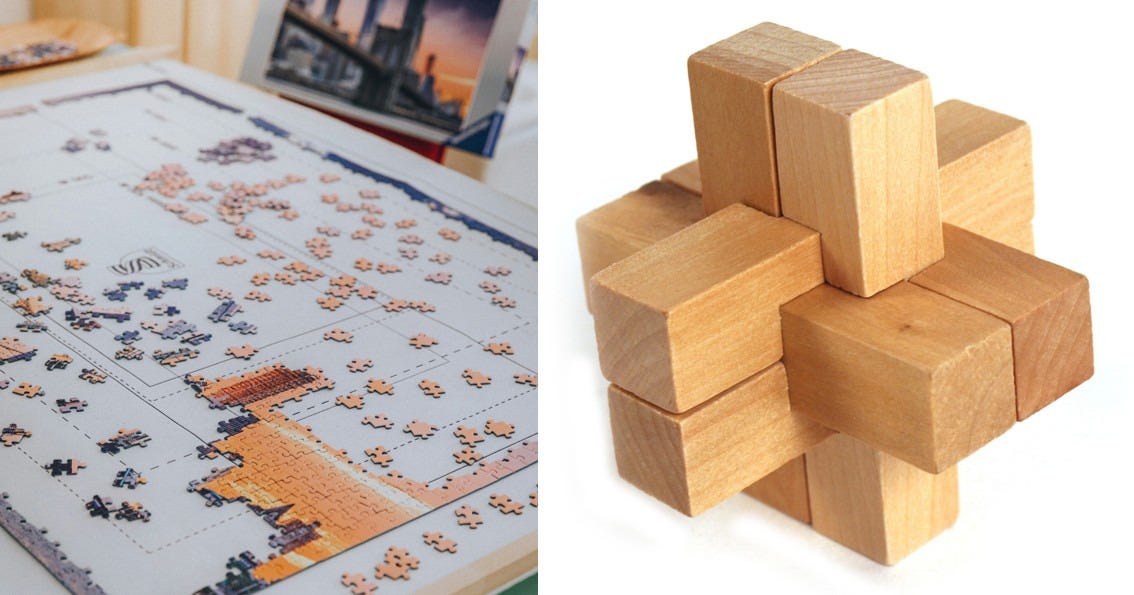

Let’s explain this by way of analogy. Imagine you have a two-dimensional puzzle, the ones of cardboard that depict an image when you fit together all the pieces. Children still have difficulty putting all the pieces together and it requires some experience before they understand this simple mechanism. It also takes some time before they understand strategies that make solving the puzzle easier, for example like focusing first on the pieces at the edge of the puzzle. Yet, no matter how difficult you make the puzzle, by changing the image or by increasing the number of pieces, the problem itself and the required mechanism to solve it does not change.

Now introduce a completely novel puzzle like a Rubik’s cube. Despite the fact that this is also a puzzle, it requires an adaptation of earlier strategies to solve it. Again, you can become very adapt at solving Rubik’s cube. Just google the world record and be amazed. Adaptation is about being confronted with new types puzzles (see figure below) and figuring out how to solve them. Moreover, we should actively try to create new puzzles for our adversaries. Don’t just increase the number of pieces, make the problem itself difficult to grasp. As if your opponent encounter the (wooden) puzzle on the right for the first time.

You have to study it first and give a couple of tries before you will be able to solve it. In our world these are not puzzles but (tactical) problems. To illustrate this analogy more accurately for military purposes I will show you two examples.

The first example will show you what we mistakenly identify as being adaptive. During one of my trainings we were planning an attack, but we had some distance to cover before getting close to our objective, for which a couple of trucks were standing by for transportation. However, the training instructors decided it was a good lessons to change our plans and send these trucks elsewhere. Our plans and timeline were now in jeopardy. We therefore needed to walk all night in order to make up for the lost time. This was not good for morale, and the mood changed from energetic to exhausted and disappointed. Those trucks were within our reach.. Why did those nasty instructors need to punish us? Of course we continued and succeeded, albeit somewhat tired. Yet, what did we really learn from this training? That things do not always work out as planned, that we have more endurance than anticipated, that you need to pull yourself and your team together at times. Perhaps we would include in our future plans that transportation is not always a given and that we need a backup plan. Nonetheless, in a future event, we would not act very differently. That was also the training objective, to see if we were still able to execute the task.

My point is that no matter how hard we train, no matter how many events we script that will require a change of plans, we always stick to our common operating procedures or tactics. Moreover, we test our units to what degree they are still able to conduct them in accordance with the doctrines and handbooks. This makes sense, since most of our tactical activities are complex to execute in the first place. The result is that trainings like these make you flexible, but not necessarily adaptive.

Let’s look at another example. The Dutch army in May 1940 tried to repel the German attack on the Netherlands on key terrain, called the Grebbeberg. The Dutch army had fortified these positions with bunkers and trenches and was expecting the Germans to operate somewhat as they did in World War I. Once the Germans crossed the border with the Netherlands, the troops defending the positions at the Grebbeberg were not expecting the main attack for some days because of the expected speed and distance that needed to be crossed. It was known for example that the German artillery was still being pulled by horses. Yet, the Germans advanced incredibly fast with their motorized units, attacked on the 11th of May and were able to seize the first outposts. The Dutch responsible commander, Major-General Haberts, was convinced that this could not be the main attack. Any German attack would commence with heavy artillery barrages, which was not the case right now. General Haberts wrongly accused the Dutch troops of being cowards. These German troops were likely ‘just some rascals’. He ordered a counter-attack that failed miserably. Even after this failed counter-attack, the General continued to believe that the German main attack had not commenced. This was a grave error. The Dutch army was able to hold the defensive positions at the Grebbeberg for three days before being overrun.[11] [12] The problem here was that the Dutch troops did not understand the problem, they had an incorrect picture (model) of the enemy forces in front of them. The key is that you need to recognize when your predictions are wrong and subsequently adapt your actions accordingly. In this example the General mistakenly attributed failure to his own troops. Unfortunately, the Germans were successful by denying the Dutch army sufficient time to adapt. Following heavy bombardments of the city of Rotterdam, causing many civilian casualties, the Netherlands surrendered at the 15th of May.

My hypothesis is that armed forces tend to focus on flexibility instead of adaptiveness. We train our troops extensively and have them undergo severe trainings where they learn how to deal with unexpected events. They learn for example how to deal with stress, fatigue, changed circumstances and above all, disappointments. Yet, in the end, we still expect our troops to conduct their tactics according to doctrines and handbooks. Otherwise, we would not be able to check whether the units passes the examination or required certification. After all, we have a check-list with tactical activities that need to be demonstrated. In other words, a focus on processes instead of outcomes. What happens is that trainings like these only widen the bandwidth of the units ability to conduct a specific tactical activity. This is what the example of my personal experience demonstrated. What we actually want is units and commanders that are able to solve novel problems. It is more important to solve the problem than to follow the correct procedures but still lose the battle, and with it, possibly many lives.

“All that remains to be said [of this important continuity in war] is that military institutions must nurture the development of an institutional learning capacity before conflicts if they wish to adapt effectively during war.”[13]

Becoming adaptive

What then, is the key to becoming adaptive? As always, I try to seek answers to questions like these outside the military domain. The brilliant philosopher Karl Popper had a thing or two to say about adaptation. Popper asserted that learning processes and natural selection are basically alike, they are about problem solving. Something I have already described in one of my earlier posts on the topic (War=problem-solving). Popper argues that the mechanism for adaptation is the same for either genetic adaptations, behavioural learning and even scientific discovery. He makes this very clear in his tetradic scheme for problem solving by trial and error elimination, as displayed below.[14]

P1 -> TS -> EE -> P2

Everything starts with a problem, signified by ‘P1’. ‘TS’ is a tentative solution, meaning that you test your hypothesis. This is then followed by ‘EE’ which stands for error elimination. This is the most difficult part because it requires that you first identify the errors and subsequently be able to eliminate them. After this, a new problem arises named ‘P2’. Some may not be comfortable with the concept of immediately getting to a new problem. Yet this is what happens in real life, be it war or science, and this is the culture and attitude we should foster. Only by accepting that new problems will inevitably arise can we be recognize errors, learn from them, and thus become truly adaptive.

“Its is asking the right kinds of questions that is the essential first step to any successful adaptation to the problems raised by a particular conflict”- Williamson Murray in Military Adaptations.[15]

Poppers scheme is also closely related to my proposed modification to the OODA loop, where I argue that we ought to start with Predictions, followed by Actions, corrected by Indicators (prediction error minimization) which leads to updates to our Models and to new predictions (PAIM loop). For more, read here.

So what?

What we need to do more is train against adversaries that employ novel or unexpected tactics. Focus on the problem-solving skills of units and their commanders, instead of their ability to reproduce a tactical procedure or activity. We tend to focus too much on the process and too little on the product. This can be solved by allowing more free-play in command post exercises, something Jim Storr also advocates in his book ‘Something Rotten’.[16] We should test units and commanders on their ability to adapt. Those who deviate from common procedures and doctrines while still being successful should be rewarded for it. Solving problems, and creating problems for your adversary, should be the focus.

The dilemma is that units first need to know what the basics are, and establish an common understanding of these basics, before being able to deviate from them. But will you then still be able to deviate or do you risk becoming entrenched in your very own creations? The more clearly you define the box and make yourself familiar with this particular box, the more difficult it becomes to ‘think outside of this box’.

There are on top of this two more obstacles that make the adaptation difficult to achieve: leadership and culture. As I have written in my post on cognitive diversity, leaders do not always listen to their subordinates, even (or especially) when they offer information that might counter their orders or believes. The example of the Dutch Major-General Harberts in World War II exemplifies this problem.

Culture possibly has a large influence on your ability to become adaptive. Some hierarchical cultures favour strong leaders that do not easily admit their faults, let alone subordinates pointing them out. How can you become adaptive, if you are not willing and open to learn from your mistakes?[17] Despite the assessment that most Western cultures are less hierarchical and therefore possibly more adaptive, our military cultures still have much work to do on becoming more adaptive. Becoming adaptive is not some drill or procedure you can follow. It has more to do with a command climate that allows you to recognize and identify errors and then adjust to them. Mick Ryan: “It requires a cultural predisposition to learning and sharing lessons widely, accepting failure as an opportunity to learn, and a well-honed understanding of risk.”[18] We must however embrace the fact that we will be wrong, and that we will make mistakes, one way or the other. Better to identify them quickly and adapt than to cling to your honour and perish. As general Stanley McChrystal argues:

“The first step is to identify our cultural problem… Military leaders must combine a level of elasticity and big-picture thinking when confronted with new styles of conflict. Accordingly, we must come to terms with the fact that following yesterday’s rules of war will not lead to today’s (or tomorrows) success – that awareness alone can save lives.” Gen. Stanley McChrystal (Ret.)[19]

The views expressed are those of the author and do not reflect the official position of the Armed Forces.

[1] Mick Ryan, The War for Ukraine: Strategy and Adaptation under Fire, P218

[2] Mick Ryan, The War for Ukraine: Strategy and Adaptation under Fire

[3] https://americanmilitarynews.com/2022/02/videos-show-multiple-russian-attack-helicopters-shot-down-in-ukraine/

[4] https://www.armyupress.army.mil/Portals/7/military-review/Archives/English/Online-Exclusive/2023/Graveyard-of-Command-Posts/The-Graveyard-of-Command-Posts-UA2.pdf

[5] https://www.nytimes.com/2022/05/13/world/europe/ukraine-russian-forces-pontoon-bridges-river.html

[6] Sean McFate, Goliath: Why the West isn’t winning. And what we must do about it. P11

[7] He also speaks of the nihilists, but this group offers little in explaining the problem.

[8] Sean McFate, Goliath: Why the West isn’t winning. And what we must do about it. P14

[9] Sean McFate, Goliath: Why the West isn’t winning. And what we must do about it. P17-20

[10] Philip E. Tetlock & Dan Gardner, Superforecasting: The Art and Science of Prediction

[11] https://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Slag_om_de_Grebbeberg

[12] Battlefield tour and instruction at the Grebbeberg in 2024 as part of the Dutch Army Staff College.

[13] Mick Ryan, The War for Ukraine: Strategy and Adaptation under Fire, P218

[14] Karl Popper, The Cambridge Companion to Popper, edited by Jeremy Shearmur and Geoffrey Stokes, P76

[15] Mick Ryan, The War for Ukraine: Strategy and Adaptation under Fire, P115

[16] Jim Storr, Something Rotten: Land Command in the 21st century P219.

[17] https://open.substack.com/pub/democura/p/how-cognitive-diversity-can-help?utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=web

[18] Mick Ryan, The War for Ukraine: Strategy and Adaptation under Fire, P111

[19] Sean McFate, Goliath: Why the West isn’t winning. And what we must do about it. PXIV

Bibliography:

- Jim Storr, Something Rotten: Land Command in the 21st century (Hampshire: Howgate Publishing Limited, 2022)

- Karl Popper, The Cambridge Companion to Popper, edited by Jeremy Shearmur and Geoffrey Stokes (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2016)

- Mick Ryan, The War for Ukraine: Strategy and Adaptation under Fire (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 2024)

- Sean McFate, Goliath, Why the West isn’t winning. And what we must do about it. (UK: Penguin Random House, 2020)

- Philip E. Tetlock & Dan Gardner, Superforecasting: The Art and Science of Prediction (New York: Penguin Random House, 2015)

Photo 1: AI (DALL-E)

Photo 2: Photo by Bianca Ackermann on Unsplash

Nice piece. One suggestion would be to make a distinction between tactical adaptation, where that succeeds and fails, and then where flexibility (rather than adaptation) comes into play. Recommend a look at Finkel’s work On Flexibility. Lastly, I’m not sure the lessons learned from other wars is quite as straightforward as Ryan and others allege. Worth reading Bruce Sterling’s Other People’s Wars.

At first glance the differences between the meanings of flexibility and adaptability seem almost pointless to belabor, but one of the hallmarks of thought provoking military theory is to use established vocabulary to reorient understanding. It’s useful exercise and calls to mind the old joke about the two psychiatrists passing in a corridor when one of them says, “Hello”…and as they continue walking in their respective directions the second think to himself, “I wonder what he meant by that”. The usefulness of reading a wide range of authors including from other countries is to cultivate flexibility of mind and openness to differing ideas and perspectives.