Sharpening our Military Command, Part II

Why more information and more personnel does not necessarily create better command systems.

We intuitively think we need more information and more (specialized) staff on military command posts in order to become more effective. In this post I will argue that this is not necessarily the case. Instead, I will argue that we should always actively try to minimize the amount of information and people necessary for command systems to operate effectively.

Explaining our current command systems.

How come that we have continued to enlarge our command posts since the second world war and crave an ever larger amount of information? One of the possible reasons is that we have had the luxury to do so. The past decade or more, our command posts have not been vulnerable. This makes it easy and safe to add one or two more staff officers. An article in the Military Review (US Army) written in 2023 by Lt. Gen. Beagle, Brig. Gen. Slider and Lt. Col. Arrol, (U.S. Army) tells us: “Those combat training center “lessons,” appropriate though they were for that time and mission, inculcated an entire generation of leaders with a sense of invulnerability inconsistent with highly dynamic, mobile, and lethal warfare against a capable enemy.”[1]

Another possible reason is that our missions demanded more tasks than Large Scale Combat Operations (LSCO) previously did. We for example needed to train national troops, as we did with the Afghan National Army (ANA) in Afghanistan. We supported local development projects, on infrastructure, health and local governance, for which we created Provisional Reconstruction Teams (PRT). All these kinds of tasks required new experts and thus additional staff.

The increased availability of more information, as a consequence of new information technologies, also required more staff for processing. Not to mention the support needed for installing and sustaining the CIS. When I was working at a Brigade HQ some years ago, it took two days (!) to install the necessary network in a large tent, which as a consequence could not be moved in short notice. Fortunately we have currently already radically changed this concept and the speed it takes to get an HQ up and running (albeit still not enough), yet the anecdote exemplifies where we came from.

Some argue that we needed more information because of an increased complexity. This is partially true, as I explained in this post on ‘Our fixation on complexity’.

We simultaneously have become very adept at creating elaborate processes (eg. MDMP, COPD[2]) that demand products for our commander and staff like the Mission Analysis Brief. These products sometimes result in meticulous PowerPoint decks, for which the briefing ‘of course’ first needs to be rehearsed before presenting it to the commander. Jim Storr goes as far by arguing that “regrettably commanders and staff fell back from intuition onto process because process was sociologically faultless (or blameless).”[3] Lt. Gen. Beagle et al. can add to this view: Commander’s experience, knowledge, and intuition today are backstopped by an unprecedented system of functional experts and technical tools that significantly reduces their decision risk but exponentially increases risk to mission and their personal safety.[4]

Jim Storr also has a take on this: “HQ’s became larger (and slower) for several reasons. They conduct more functions (but not many: and some are invented); that they are micro-managed; they plan in more detail; and plan further into the future (which is generally mistaken). That is, they over plan and keep people in jobs. The micro-management mostly results from having too many senior officers in the HQ”[5]

To conclude, there are several possible explanations (and likely many more) for how we got to large command posts in need of large amounts of information. However, there are good reasons why we should abandon these practices when preparing for LSCO. Earlier LSCO like the second world war did clearly not have command posts as large and elaborate as we see know (see earlier post on the need for faster and shorter orders). The following quote of Lt. Gen. Beagle et al. gives a good summary: “Sometimes, evolution includes mutations that, if left unchecked, can metastasize into a vulnerability that requires a revolution to correct. Such is the case with U.S. command posts over the last twenty years, which have been rendered unfit for their purpose given the speed, complexity, and lethality of large-scale combat operations.”[6]

Current Command Post Paradigm?

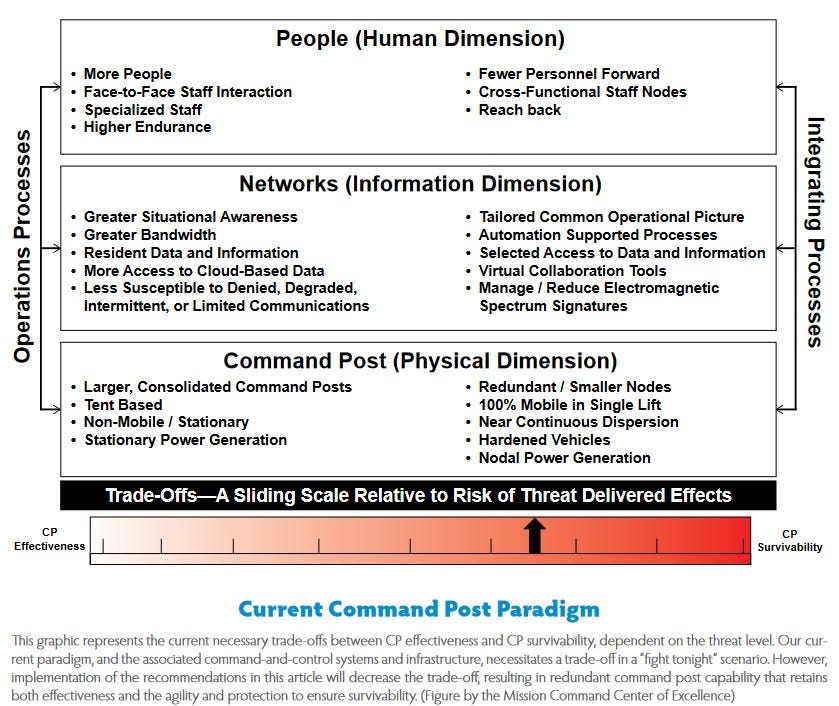

Let us look at this intuition of why we think more information and more specialized staff increase the effectiveness of command systems. The article by Lt. Gen. Beagle et al. will provide some insight into this intuition and what they call the Command Post Paradigm.[7] The article explains that the war in Ukraine has shown us that our command systems will remain vulnerable to enemy fires and the like, hence the title of the article: The Graveyards of Command Posts. If we want to survive, we need to make concessions to our current command systems. The authors argue that there is a trade-off between a command post (CP) effectiveness and CP survivability. The figure below shows that there is a sliding scale when it comes to the number of people within a CP, the amount of information it can access and process, and the physical dimensions such as size. These three factors influence the effectiveness on the one hand, and vulnerability on the other on a sliding scale.[8]

It is reasonable to argue that a smaller CP is less vulnerable, especially if you can create several redundant CP’s instead of one large CP. A larger and more static command post on the other hand is easier to manage and equip and thus more likely to be effective. The other two factors are less clear-cut. For instance, more people and more information do not necessarily result in a higher effectiveness. Having less personnel and reducing electromagnetic spectrum signatures however do have a positive effect on the survivability. Lt. Gen. Beagle et al. argue that the trade-off can be decreased and propose several viable solutions, albeit mostly technical in nature, despite emphasizing the importance of the human dimension in CP’s. This superb article in my opinion only got one thing wrong: less personnel and information are not necessarily a trade-off, they are worth pursuing in itself in order to become more effective.

Less information and less personnel.

Let’s start with why less information can be more effective. More information is generally not the answer. The answer is better information at the right time. Knowing what that is and how to find it requires experience, skill and judgement. Storr: “Any apparent demand for more information tends to be a sign of poor commanders, poor processes, and over-large staffs.”[9] We already face situations where we give our troops an overload of information. Take the fighter-pilots of F-35 jets for instance, they have so many sensors aboard that they simply can’t process the data, nor apparently can entire ground crew teams of analysts at the moment.

There is also the problem of what we tend to report. We have a tendency to report ‘every tree’ instead of reporting only the ‘wood’. We need to start passing knowledge instead of data. Yet this implies that the reporter knows that he is reporting a wood, not a hundred trees.[10] There is a difference between critical information and contextual information. Whereas the critical information is necessary for the subordinate or one-up to make decisions, the contextual information is often nice to know, not need to know.[11] When you believe in mission-command, and apply this effectively within your unit, you will likely need only limited amounts of critical information to pass on. What we often do however is communicate enormous amounts of contextual information. This was not a problem in the past decade or so, but it can now become an obstacle in LSCO where we risk become a target when we broadcast in the electromagnetic spectrum.

“If you keep sending a command post reports of trees, it will start to see lots of trees; and then it reports lots of trees to its superior HQ. This may result in big picture blindness: not seeing the wood for the trees.” Jim Storr

Trials have also shown that the quality and quantity of information make very little difference to the outcome of decision making. This may sound counter-intuitive. What they showed was that the personality, experience and skill of the decision maker has far more impact.[12]

What about personnel? The most obvious mistake is that we often think that by throwing extra people at some problem, it will therefore be fixed more effectively. Storr provides a very stark and sobering picture: “Observing command posts over a series of exercises revealed that typically 40 percent of the people do something of value. 20 percent do nothing of value. 30 percent do something of value. 10 percent do something counterproductive. That can be astonishingly disruptive. In a good command post 60 percent do nothing of value; the other 40 percent are more effective because they can ignore the others.”[13] Some might not agree with Storr on this picture, and I doubt whether these numbers need to be taken that seriously. Yet, we all have examples of people in our workplace that do much, some that do little, some that even do something counter-productive. It does not matter if you work in industry or some sales company. I even doubt that this is a problem of military CP’s exclusively. The difference however is that in LSCO, we don’t have the luxury of being complacent on these matters. There is only one outcome in LSCO, win or be defeated.

I also want to highlight the point made by Storr on the additional functions CP nowadays have compared to the second world war. We already concluded that this was largely a consequence of the type of missions from the previous decades. The question now is whether we need all these functions in LSCO. Civil Military Cooperation (CIMIC) is one of those functions which has a different and more limited role in LSCO. We definitely need the function, yet not in the decisive first 72 hours of battle and not at the Forward CP.

Martin van Creveld’s observed in his book, ‘Command in War’ that highly centralized organizations impose high information demands on their subordinates. Organizations can respond in two manners. By increasing their information processing capacity or by designing the operation to operate on less information.[14] We have clearly done the former, where we should do the latter. Mission-command and working with a commanders’ intent are tools that solve this problem and which we already have at our disposal. The problem is that we do not always apply them as they are intended. Moreover, creating CP’s with too many staff officers, supported by large bandwidth CIS, will likely result into over control and thus less mission command. Of course, this need not be the case if you instruct your staff well, but by denying the possibility to control, we are forced to design the operation for mission command pur sang. To give just one example, I have seen many CP where the staff is looking at some screen from an UAV overhead. This makes great movie scenes but makes no sense in real military operations. The most important thing is that the commander on the ground has the information collected by the UAV and can hence make well-informed decisions. Having superiors look at these live images invokes over control. As an extreme example to give you a sense of what I mean, just look at the image below which shows the President of the United States and his staff watch the operation to take out Bin Laden.

To conclude, less personnel and information are not necessarily a trade-off between effectiveness and vulnerability. We need CP’s that are less reliant on information and require less personnel to operate because this will benefit the effectiveness of the command system. In the first part of this series on command systems I already stressed the importance of having shorter orders, faster. If we combine these two premises, then less personnel and less information will allow us to create faster and shorter orders. We need to report only one single wood, instead of a hundred trees.

[1] https://www.armyupress.army.mil/Portals/7/military-review/Archives/English/Online-Exclusive/2023/Graveyard-of-Command-Posts/The-Graveyard-of-Command-Posts-UA2.pdf, P6

[2] MDMP: Military Decision Making Process, COPD: Comprehensive Operational Planning Directive.

[3] Jim Storr, Something Rotten: Land Command in the 21st Century, P160

[4] https://www.armyupress.army.mil/Portals/7/military-review/Archives/English/Online-Exclusive/2023/Graveyard-of-Command-Posts/The-Graveyard-of-Command-Posts-UA2.pdf, P6

[5] Jim Storr, Something Rotten: Land Command in the 21st Century, P128

[6] https://www.armyupress.army.mil/Portals/7/military-review/Archives/English/Online-Exclusive/2023/Graveyard-of-Command-Posts/The-Graveyard-of-Command-Posts-UA2.pdf, P6

[7] https://www.armyupress.army.mil/Portals/7/military-review/Archives/English/Online-Exclusive/2023/Graveyard-of-Command-Posts/The-Graveyard-of-Command-Posts-UA2.pdf

[8] https://www.armyupress.army.mil/Portals/7/military-review/Archives/English/Online-Exclusive/2023/Graveyard-of-Command-Posts/The-Graveyard-of-Command-Posts-UA2.pdf, P2

[9] Jim Storr, Something Rotten: Land Command in the 21st Century, P149

[10] Jim Storr, Something Rotten: Land Command in the 21st Century, P146

[11] Jim Storr, Something Rotten: Land Command in the 21st Century, P150

[12] Jim Storr, Something Rotten: Land Command in the 21st Century, P149

[13] Jim Storr, Something Rotten: Land Command in the 21st Century, P128

[14] Jim Storr, Something Rotten: Land Command in the 21st Century, P201

Picture 1: Created by AI (Microsoft Image Creator)

Picture 2: https://www.businessinsider.com/situation-room-osama-bin-laden-2011-5?international=true&r=US&IR=T

Bibliography:

Jim Storr, Something Rotten: Land Command in the 21st century (Hampshire: Howgate Publishing Limited, 2022)

https://www.armyupress.army.mil/Portals/7/military-review/Archives/English/Online-Exclusive/2023/Graveyard-of-Command-Posts/The-Graveyard-of-Command-Posts-UA2.pdf